Backyard, Monolith 2020

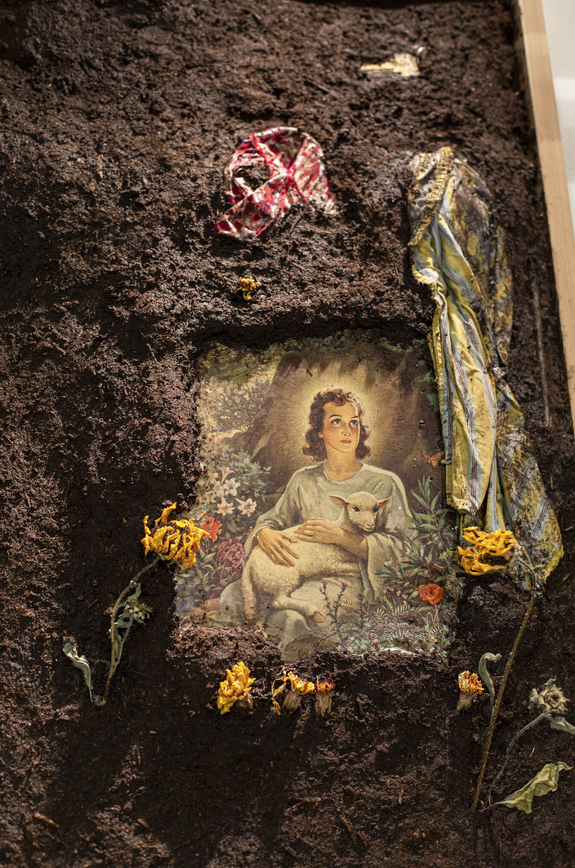

Cedar, soil, reclaimed wood platform, clamp light, dried flowers, personal historical artifacts.

11.5ft x 2ft x 6in (Monolith), 4ft x 5ft x 5ft (platform)

Backyard, Monolith is an excavation of the history that lies in my own backyard, that in which I attempt to grow a garden. Objects are suspended in a state between excavation and burial, speaking to a felt absence. Stacked vertically, the main column structure is a gesture of the exhausting effort towards transcendence via excavation of one’s own history. My history includes the erasure of those who stood on this ground long before me. When I consider what rests beneath the soil, the history in my hometown—that is like every small town’s history, this feels like a memorial.

I imagine each panel arranged like the archaeological record, expanded so that as a viewer we struggle to see the top, which barely clears the ceiling rafts. Excavated soil is hoisted to the sky. The top panel holds my own history, my family, our recent imprint in the topsoil. Unexcavated trauma. A portrait of a sort of feminine, white Jesus [who failed to protect me]. Below lies the mark of lives lived, and the violence in their displacement and erasure. There is silence and stillness in the packed soil panels, the absence is felt. Dried flowers are placed around the uncovered objects as gesture of mourning. A haunting garden.

The platform is an object of the institution. It is both 1920’s revival pulpit and historic landmarker. And its failure to bring the viewer really any closer to the out of reach—or its inaccessibility, for that matter—is a testament to the failure of our current systems to address the unresolved historical trauma that rots like a disease in the bones of society.

From Tracing Faults

Chicago Artist’s Coalition, January 2020

“Backyard, Monolith offers an immediate access point into the exhibition and its framework. A column of framed soil traces a path from the ground up an into the space of the vaulted gallery ceiling. This monumental structure creates an implicit fault line, a rift that holds a series of unearthed artifacts that create a fragmented glimpse of the rural Midwestern landscape and culture from which they were collected. These objects and materials seem out of place in a contemporary art gallery, and magnify the dissonance between large urban cities like Chicago and the small communities that populate the rural landscape. The top frame contains a Westernized and feminine portrayal of a young Jesus Christ. This inclusion along with the supporting cast of materials points ot Davis’s Evangelical upbringing and underscores the soncervative and religiously driven temperament that steers Midwestern ideology.

In front of the monolith, a weathered platfrom provides a marginally closer view of the structure as it stretches out of reach. The design makes reference to landmark viewing platforms and also to 1920s era revival pulpits. The viewer is invited to step up unto the platform and gaze up with their body at the soil and its contents as they extend into the sky. For the artist, the experience serves as metaphor for the excavation of our histories, of excavating what’s beneath our feet as a possible key to our transcendence.”

-Jeff Robinson, curator